Mineral rights to human rights: mobilising resources from the extractive industries in Nigeria for water, sanitation and hygiene

Anddy Omoluabi, Programme Director for WaterAid Nigeria, and John Garrett, Senior Policy Analyst – Development Finance at WaterAid UK, consider how Nigeria’s natural resource wealth can better contribute to ending the country’s water and sanitation poverty.

Nigeria’s finance minister recently identified the pressing need to mobilise domestic resources to meet the nation’s infrastructure and development needs. Africa’s largest economy has had a troubled history in this area, struggling for decades to make optimal use of its natural resource wealth and high human resource potential. A new report by WaterAid and Oxford Policy Management – From mineral rights to human rights – focuses on Nigeria’s extractive industries (EI) sector, and considers how the country can better mobilise its domestic resources to provide sustainable funding for meeting citizens’ rights to water and sanitation.

Figure 1: Nigerian oil and gas fields

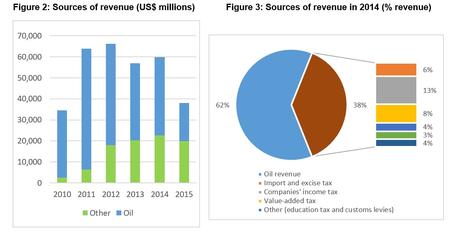

Since petroleum was discovered in the Niger Delta in 1956 it has dominated the Nigerian economy, with oil and gas production taking place today in nine out of 36 states: Abia, Akwa Ibom, Bayelsa, Cross River, Delta, Edo, Imo, Ondo and Rivers. Nigeria ranks as Africa’s largest oil exporter and the sixth-largest oil-producing country in the world, with the petroleum sector providing the lion’s share of Government revenue (Figures 2 and 3). However, weak governance, high-profile corruption cases and a disastrous environmental record have undermined the contribution of the EI to Nigeria’s economic and human development progress.

Recent external shocks to the economy underscore the need for change. The lower oil price led to a recession in 2016 for the first time in two decades, placing severe strain on the Naira, and raising concerns over debt sustainability and capacity of the Government to fund essential services. The Finance Minister highlighted the infrastructure deficits in roads, rail and power. This is also the situation for water and sanitation: less than 20% of the population have clean, safe water.

Strengthening DRM: ending theft, corruption and closing tax loopholes

How can Nigeria strengthen its domestic resource mobilisation (DRM)? The most urgent action is to stem the theft of petroleum proceeds by private individuals and groups. Evidence suggests that both physical theft of oil in the Niger delta and high-level financial crime in business and politics – have occurred on an industrial scale over decades.

Action to address the physical theft requires a combined legislative, security, social and environmental response. Elements are in place – the Petroleum Industry Governance Bill (PIGC), the US$10 billion Delta investment strategy, the Host Communities Bill, and the UN-supported $1 billion environmental clean-up of the Delta – and success will require a balance of resolve, sensitivity and external support. Disturbing research on the impact of oil pollution on maternal and newborn health and November’s tragic events show this still has far to go.

Combatting high-level financial crime requires renewed national and international efforts. The priority placed by the current federal administration to tackle corruption, to enact the PIGC, the traction gained by the Nigeria Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (NEITI) all offer promise. The tenaciousness of the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFFC) is also delivering results. Co-ordinated action from the EFCC, the courts and the USA and the UK has been essential in the latest high-level cases. However, serious questions remain whether high-income countries – and the jurisdictions they influence – are serious in preventing the flow of illicit funds out of Nigeria. London, Los Angeles and New York property markets and the British Virgin Islands (through facilitating the setting up of shell companies) have all underpinned illicit financial flows from the EI sector in Nigeria.

Increasing DRM from the EI also requires steps to end tax loopholes. For three international oil companies (IOCs), Shell, ENI and Total, pioneer status (an incentive for innovation) and other tax breaks provided exemption for $3.3 billion in tax payments. Inappropriate use of transfer pricing by IOCs is also estimated to cost the Nigerian exchequer hundreds of millions of dollars.

Transparency and accountability

Despite NEITI progress, transparency and accountability are still not sufficiently embedded to prevent high-level corruption. There is growing concern – reinforced by the recent Paradise and Panama papers – of the role of anonymous companies. Hidden company and property ownership is a big contributor to illicit financial flows leaving developing countries, and Nigeria needs to take steps to enforce transparency of the beneficial owners of all companies operating in the EI sector.

Nigeria’s government revenue as a percentage of GDP was only 4.8% in 2016. This is one of the lowest in the world. There is increasing evidence that countries with tax revenues below 15% of GDP cannot fund even basic state functions. However, action along the lines above could greatly strengthen DRM and progress made against the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including universal access to safe water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH).

The report also shows how the IOCs, through their corporate social responsibility (CSR) have contributed to the WASH sector. Italian IOC Agip has funded water infrastructure in 75 communities in four states in the Niger Delta. Investments have generally been limited, however, with IOCs pointing to the precarious security situation as a major hindrance. There is clearly scope for more to be done in this area.

A steep challenge

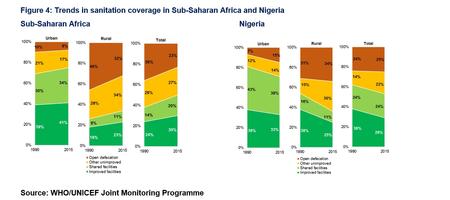

Although Nigeria met the 2015 Millennium Development Goal water target, only 19% of the population today have access to safely managed water services. There has been no overall progress in improving sanitation, with open defecation and access to shared and improved sanitation all worsening since 1990 (see Figure 4). The country faces a steep challenge in increasing access levels consistent with SDG targets 6.1 and 6.2. The World Bank has estimated the capital costs to be $10 billion a year through to 2030.

It is encouraging to see successful steps taken to identify and return stolen funds, such as the recent agreement to return US$321 million to Nigeria. A critical step to increase the incentives for the repatriation of illicit funds and the capture of increased funds from the EI could be to set up a ring-fenced fund, dedicated to resourcing the SDGs, including SDG 6. With oversight from the federal Government and civil society, it could act as a powerful mechanism and incentive for capturing additional revenues, improving public financial management and spurring sustainable development in Nigeria through to 2030.

Finally, the report argues for a long-term planning horizon. Countries that have successfully managed their EI sector, such as Botswana or Norway, have put in place effective governance, transparency and long-term planning. A failure to regulate the EI causes long-term environmental problems and ultimately undermines development, as the Niger Delta has tragically shown.

African countries have high vulnerability to the effects of climate change, due to uneven access to safe water and sanitation, dependence on rain-fed agriculture, and high levels of poverty. Nigeria has significant opportunity for hydro-electricity and solar power, and as the world seeks to effect a transition to a low-carbon economy, the country should think carefully about its energy mix, and what this entails for the management of its EI and effect on its oil revenue base.

John Garrett tweets as @johngarre and WaterAid Nigeria as @wateraidnigeria

Information in this blog has been updated on 12 December 2017.